Florida Barge Canal

The Florida Barge Canal: Water, Progress, and a Slow Death

“this canal is a bad decision but I have committed myself to it and must go ahead.” -Senator Claude Pepper

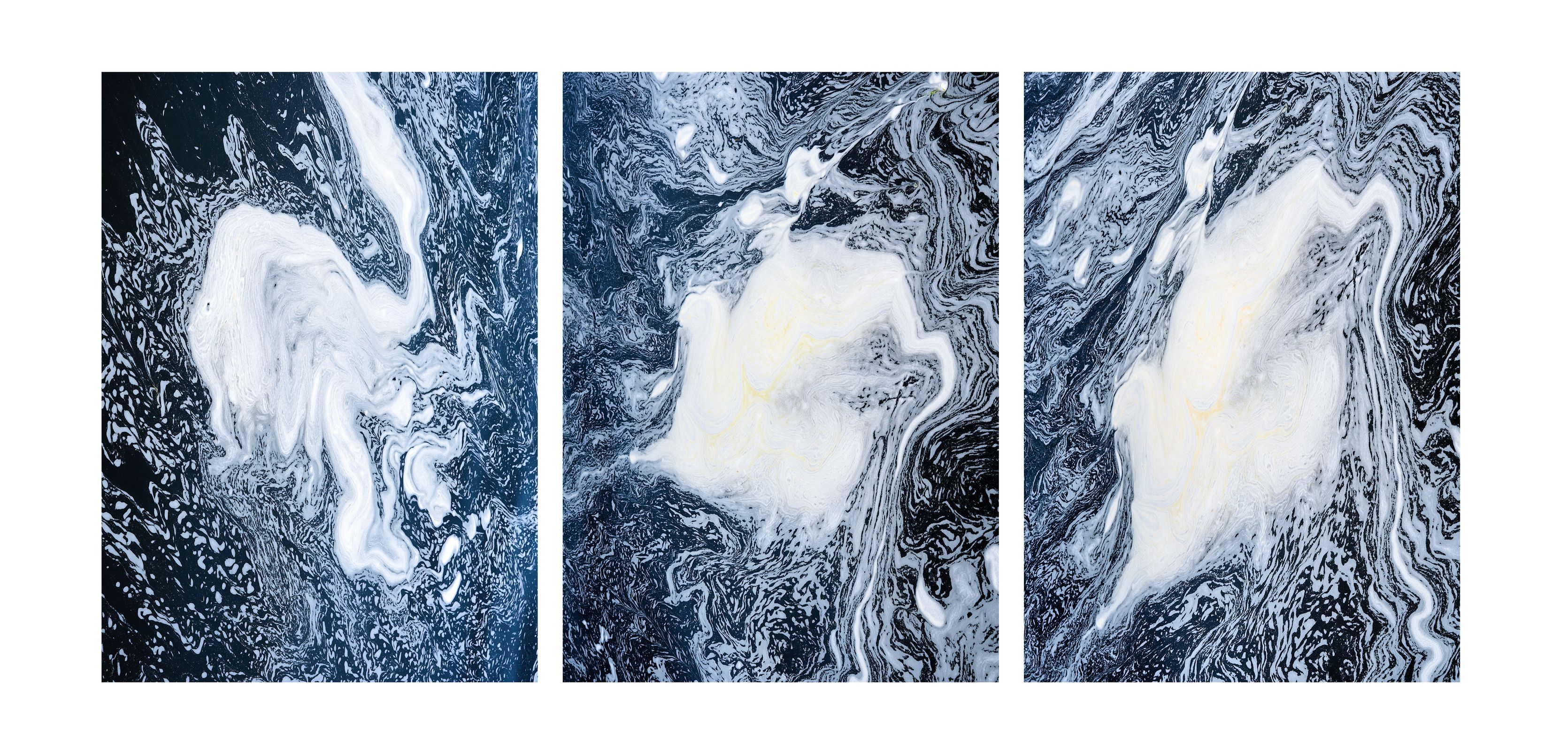

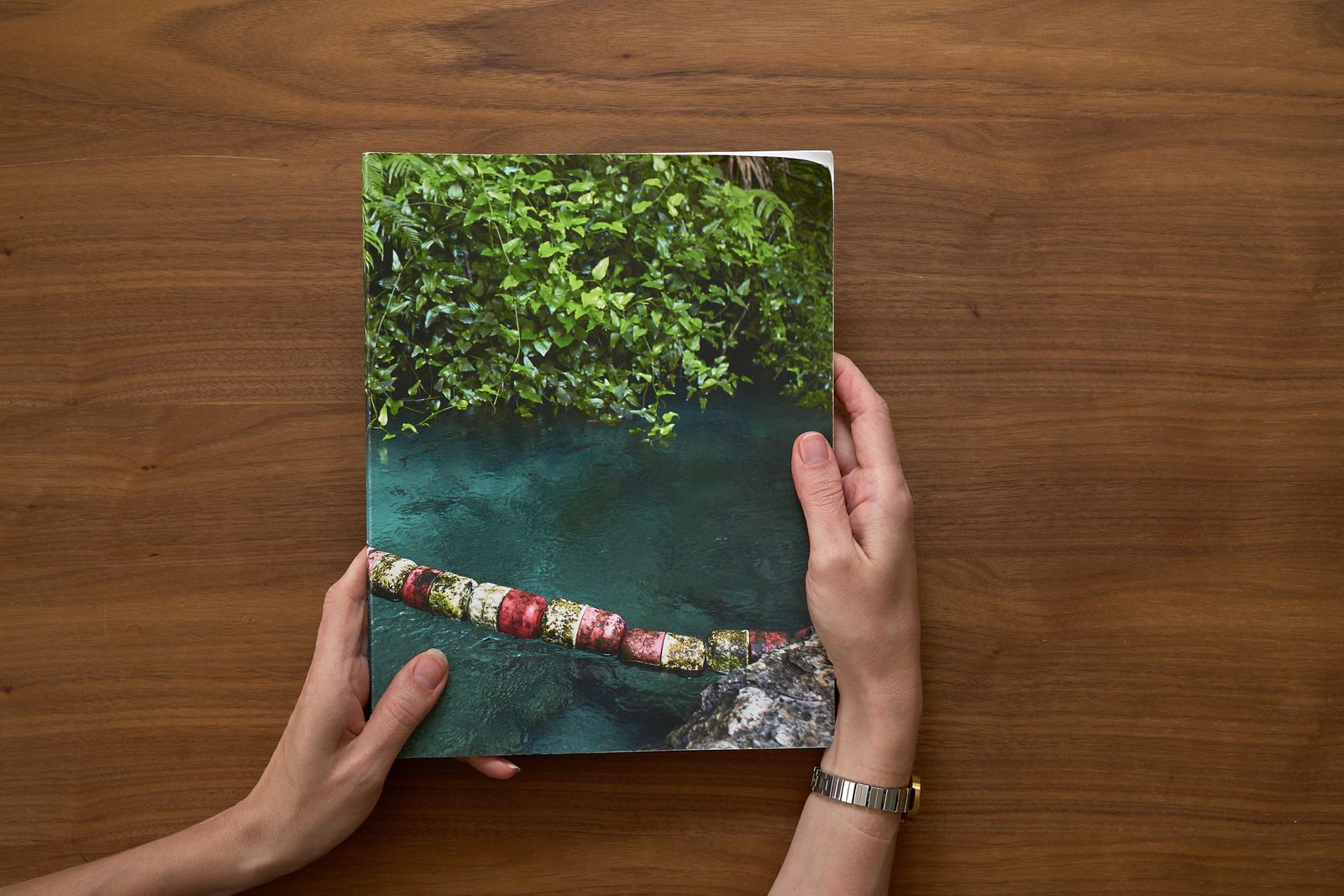

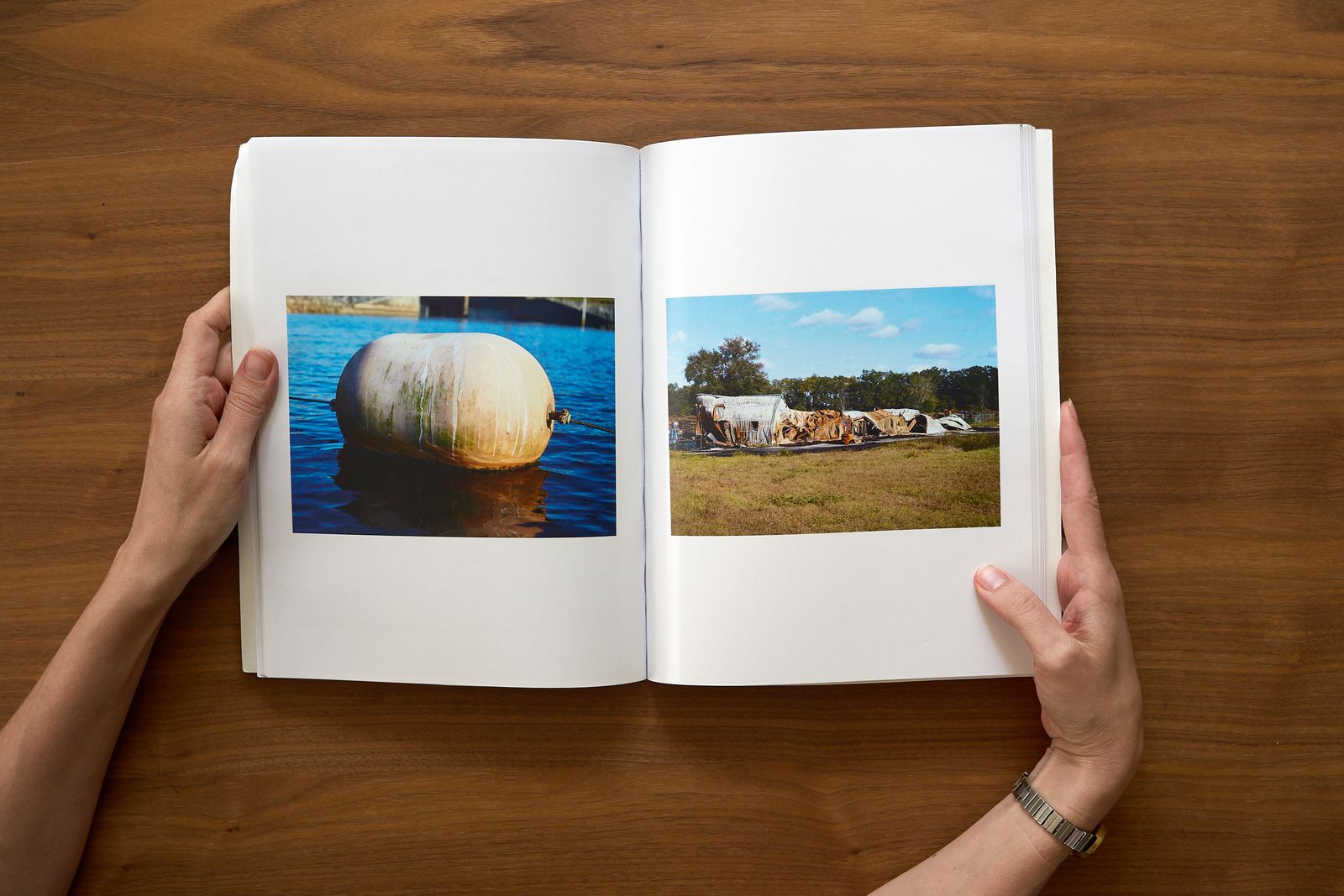

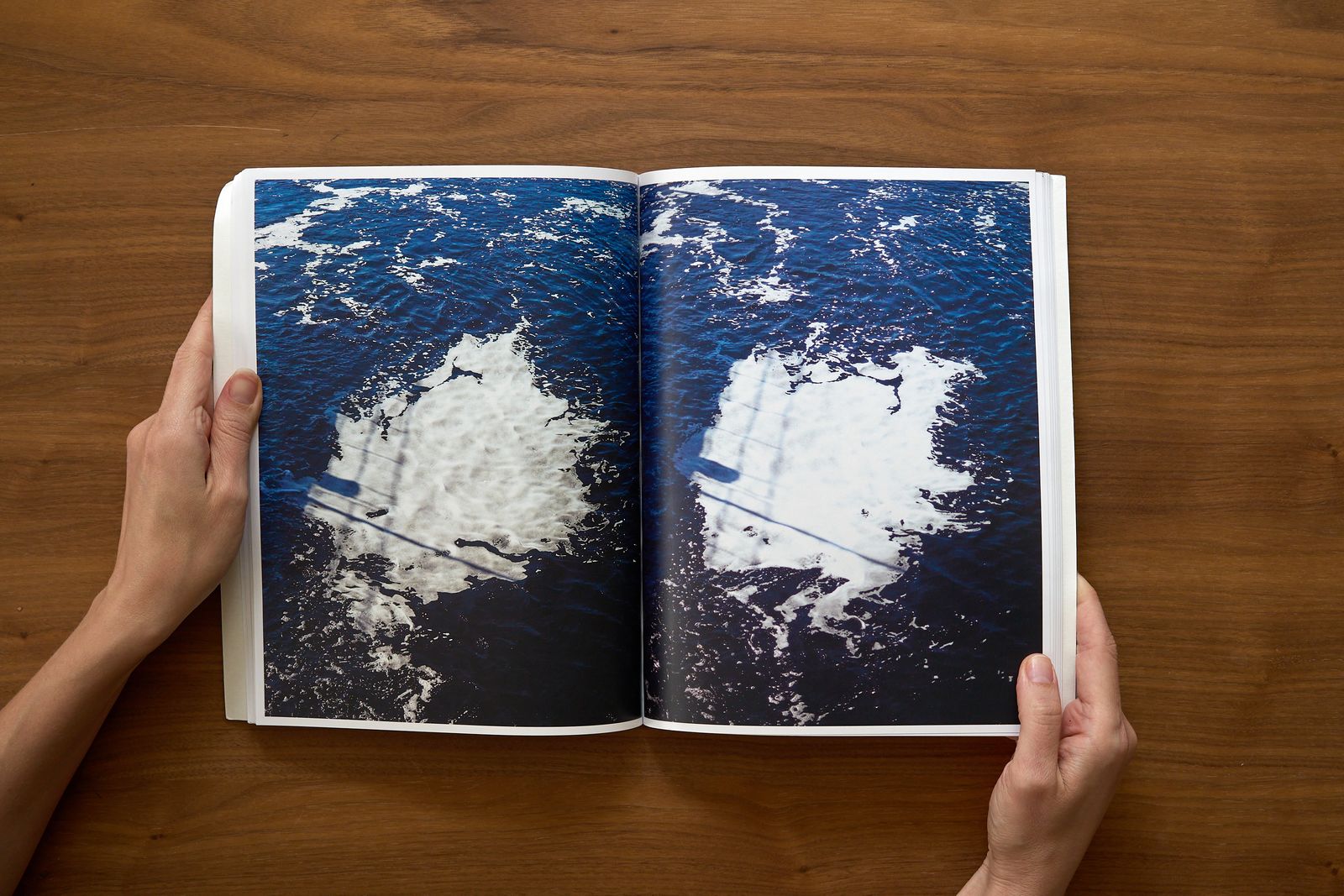

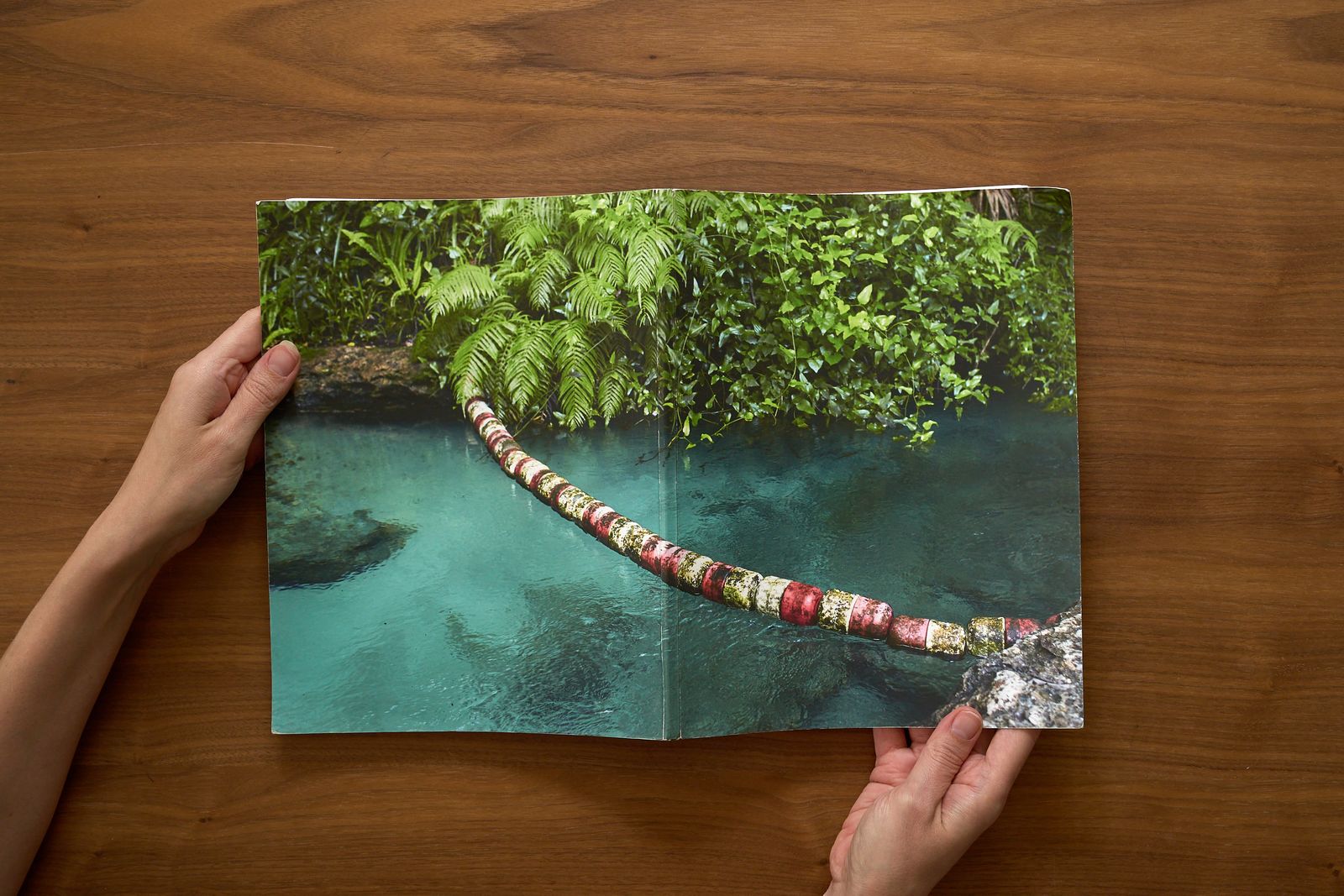

The Florida Barge Canal, an attempt to connect the Atlantic Ocean to the Gulf of Mexico, is one of the largest and most expensive failed public works project in United States history. Over 80 years after construction began and with 30 percent of the project completed, this complex system of defunct canals, dams, locks, reservoirs have become concrete monolith structures in the Florida wilderness. However, the derelict barge canal sites have developed their own eco-systems, and conservationists and environmentalists are at odds over which environment deserves to stay and which should be erased. The photographs in this project document these derelict sites scattered across Florida, but more broadly, visualize the domino effect of misguided policy.

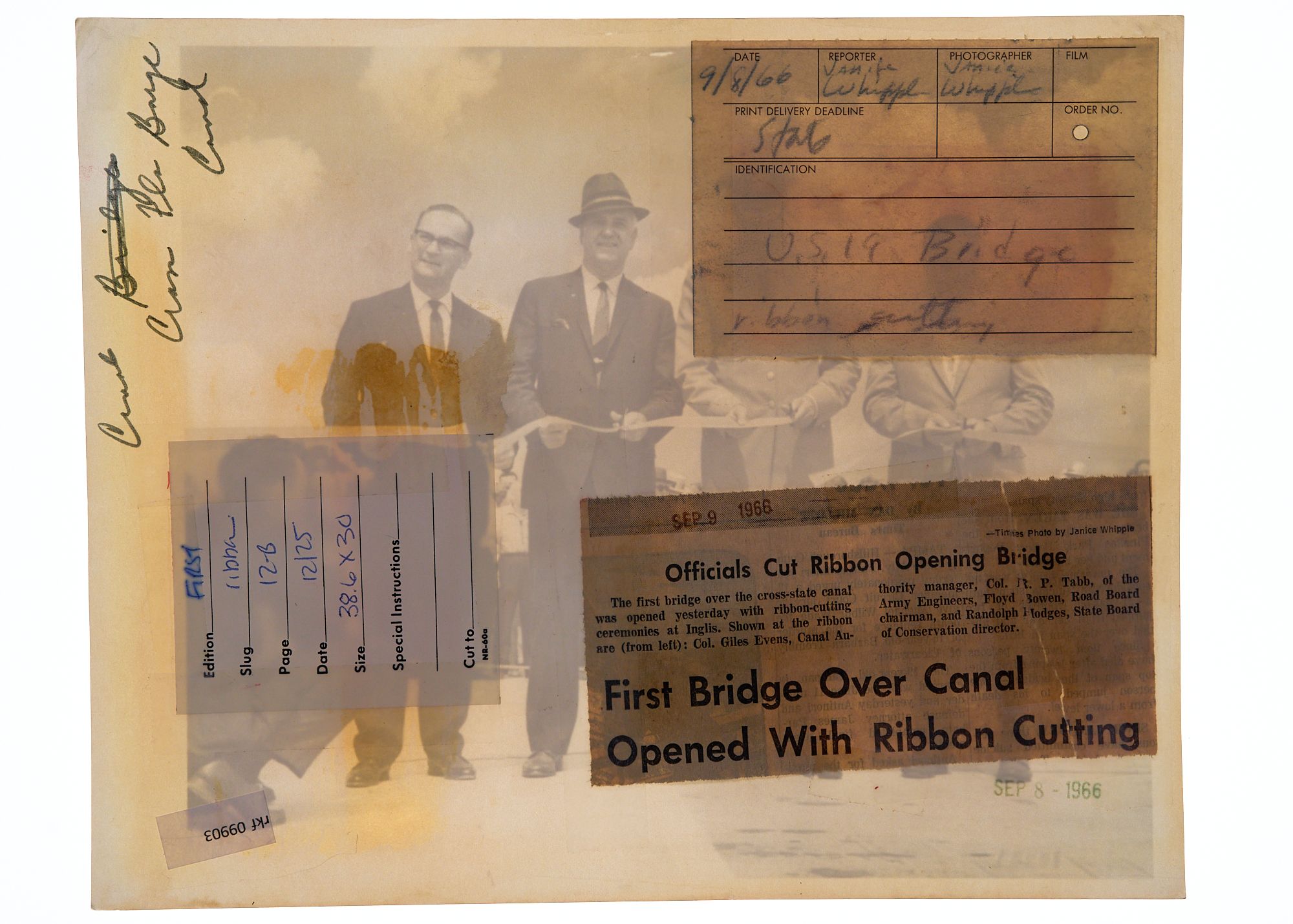

Since the earliest Spanish explorers hacked trails through palmetto brush, various colonial administrators and imperial governors dreamt of safe passage between the Atlantic Ocean and the gulf of Mexico. In 1935, progressive politics and New Deal era–funding initiated the long awaited Trans-Florida Canal. Although railway lines ran throughout Florida, a canal would add to the existing infrastructure and modernize the dense and swampy landscape in an effort to bring industry to the burgeoning towns in central Florida. The canal route determined by the Army Corps of Engineers required thousands of acres of land be cleared and flooded. This massive work effort displaced entire towns, most notably the freedman town of Santos. The townspeople, black share-croppers descended from emancipated slaves, were coaxed into selling their land to the state for pennies on the dollar along with jobs helping to clear the land.

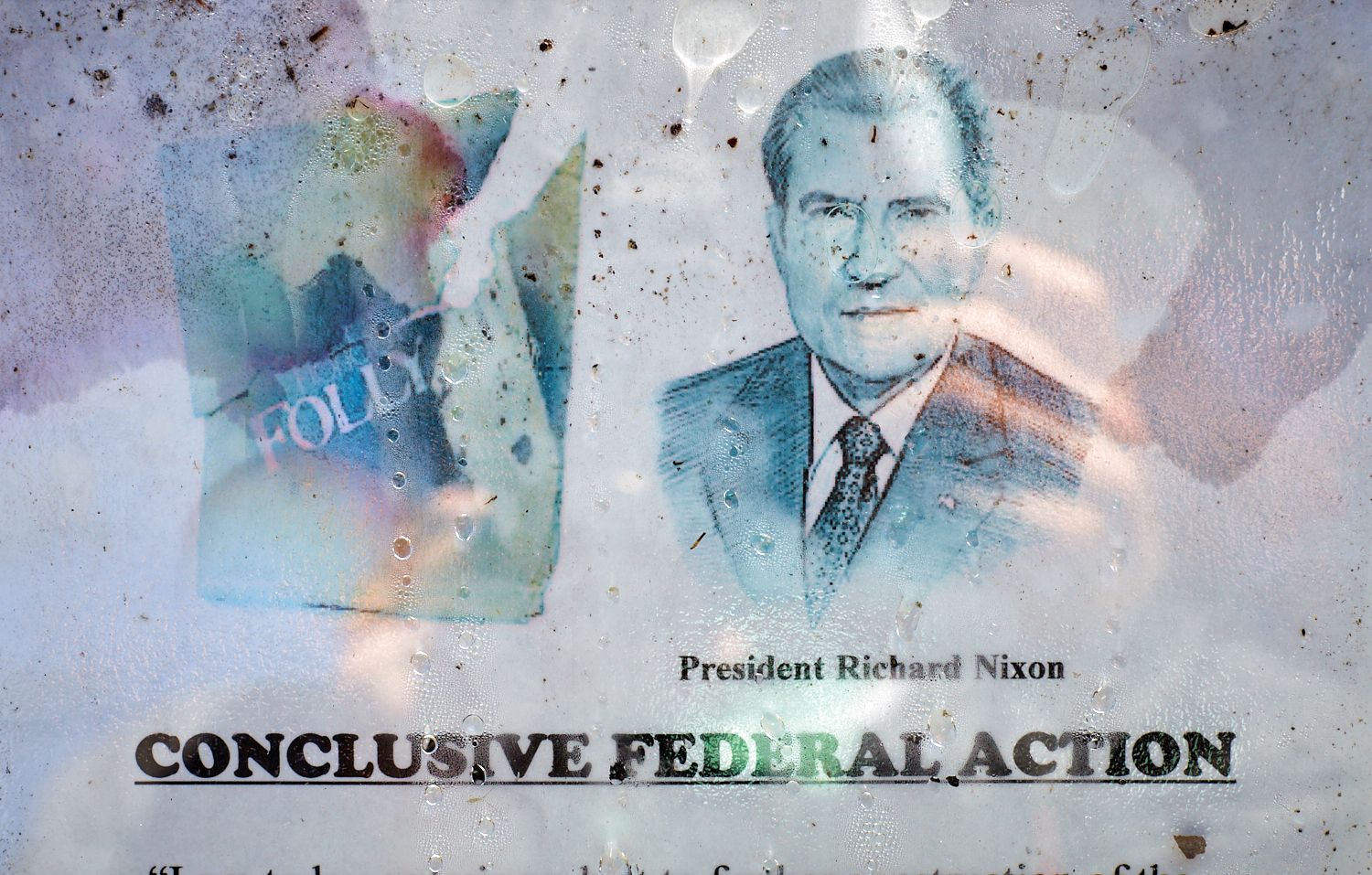

Throughout the canal’s history, both promoters and dissenters used the ideas of progress, sustainability, and local interests to champion their cause. After only a year of rapid construction, one-third of the canal route was completed. Afterwards came years of protests, underfunding, and congressional acts which brought the canal to an ambiguous slowdown. In 1971, President Richard Nixon cancelled the project, which marked the success of environmentalists who alerted Floridians to the threat of salinization to the state’s aquifer, the backbone of the its economy.

Environmental issues and sustainability efforts are often characterized by two opposing arguments: building or not building, preserving or destroying. Attempts to demolish the sites to bring pre-canal landscapes back have people facing tough questions. Which landscape is original, more important, and what’s the right thing to do? The photographs in this project explore what happen when political agendas sideline communities, leaving social and environmental questions unanswered almost a century later.

Artist Book, "Monoliths Among Palmettos"

8.5" x 11" Color Laser Prints using Perfect Bind, ed. 4

Exhibition Installation

Galveston Arts Center, 2025